Maria Kennedy is a PhD Student of Folklore at Indiana University. She spent a year and a half living in the UK while conducting field research for her dissertation. She has often found reprieve from the book-bound aspects of the academic life in fields, vineyards, orchards, and gardens, working on farms in the UK (Ross on Wye Cider and Perry), upstate New York, and Indiana. She first became interested in historic cookery and agriculture while working at Conner Prairie Living History Museum in Indiana, where she learned the fine arts of hearth cooking, butchering, and natural dyeing. You can keep up with her cider adventures on her blog, Cider With Maria.

It’s time for Wassail, the celebration of cider and orchards on the 12th Night of Christmas, which according to different calendars can be either the 5th or the 17th of January. This custom, which almost died out in England, happens in the dark period of winter when the nights seem to become interminably long. People bearing torches process into an orchard lit with twelve bonfires representing the twelve months of the year or the twelve apostles. They sing to the trees, scare away evil spirits with gunshots or banging old pans, and share a drink of good health from a communal wassail bowl.

Wassail is an old word from Anglo Saxon meaning “Good Health,” and throughout the celebration, participants frequently shout it with lusty exuberance to toast each other and the health of the orchard. Contemporary wassails often include members of the local Morris group, who lend performances of traditional music and dance, as well as outlandish costume and rowdy humor, to the event.

Experience has taught me that this English custom is pretty flexible in almost every way, however, and just about anytime in January will do when you need an excuse to blow off some steam after the formal Christmas holiday.

Wassail in England is centered around the celebration of orchards and the wine made from their fruit — cider. Hard cider is booming in the North America, but the custom is fairly unknown here! I came around to the world of cider quite by accident while doing ethnographic field research in the UK on the subject of environmentalism, cultural heritage, and agricultural land management. I just happened to end up in an orchard region of the UK, and I began to find myself drawn into the world of traditional orchards, orchard conservation, and inevitably, craft cider making.

Having spent time drinking cider on both sides of the pond, I’ve pondered a bit on the differences in cider culture between the US and the UK. The writing and photography team of Bill Bradshaw and Pete Brown have just published a great book this year called World’s Best Ciders, which I would recommend to anyone who wants to get an introductory grasp of the global cultures of cider. It is exciting, especially for someone like myself with an interest in folklore and anthropology, to survey the myriad cultures of apple growing and fermenting around the world.

What impressed me most about the culture of cider in the United Kingdom, as opposed to the United States, were the deeply-rooted histories of regionality, agriculture, class, and gender that are woven into the meaning cider. Britons, who live in a much more densely populated country than us, where the pathways from city, to market town, to village, to hamlet, have been trodden for over a thousand years, have an incredibly deep and detailed cultural imagination about their rural places, their countryside, and even their apples.

From the rise of scientific agriculture in the Enlightenment years of the 17th century, but before the explosion of industrial agriculture after World War II, English landowners encouraged and supported a highly evolved culture of farming and gardening which sought to improve production and develop new crop varieties through plant breeding and technological advancement. This reached a luxurious pinnacle in the cultivation of exotic fruits such as the pineapple within the greenhouses and walled gardens of aristocratic classes.

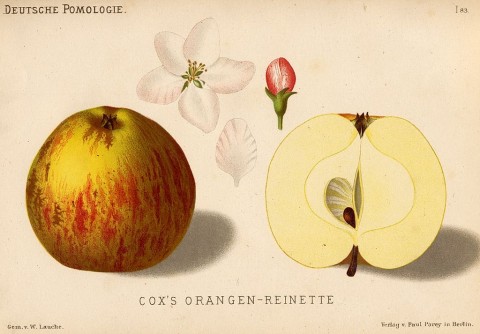

In this environment, many varieties of apples and pears flourished, some developed and grown very locally, others, such as the Cox’s Orange Pippin, an eating apple, or the Bramley, a cooking apple, which spread nationally. A large variety of cider apples, rich in tannins which contributed to superior fermentation and storage, were also cultivated in particular regions, particularly in the south and west counties of Devon, Somerset, Gloucestershire, and Herfordshire.

During the heydey of the Enlightenment, cider and its cousin perry were a drink of gentlemen, a national drink made of the island nation’s own produce. After the Napoleanic wars though, the aristocracy returned to its love for extravagant foreign wines, and cider became a common drink of farmers and laborers, a self-sufficient product made and consumed by families from the orchard fruits of their farms and small-holdings.

So what does this mean for cider today in the UK? I found my way into a seasonal job at a cider farm in Herefordshire and made friends with many local cider makers there. At the heart of cider making in all cases, from the hobby producer to the commercial enterprise, is the seasonality of the drink. It is a year-long labor of love, seeing the orchard through its many cycles, through the pruning in the winter, the anxiety of the budding, blossom and fruit set under the threat of spring frosts, the mowing beneath the trees in the summer, the early-morning spraying in the still air, and the torrent of work in the harvest and pressing season in the autumn.

Unlike beer, which can be brewed from stored grain at any time, craft cider can only be made at the right moment, when the apples are just ripe enough to press. Many of my cider making friends harvested from trees they had hunted down in the neighborhood, old cider trees of interesting varieties left over from that earlier era before mono-crops became the norm. With the new interest in sustainable agriculture and craft products, these old varieties are in demand again, and there is a promising trend of propagating and planting varieties that might otherwise have disappeared.

The truly devoted fan of craft cider revels in its seasonality and terroir. For many Britons, though, it is still known a cheap mass-produced drink associated with women, alcoholics, and naughty teenage indulgence. This unfortunate reputation may have resulted from its history as the drink of the rural laboring classes, but also because it as it became a mass-produced industrial product, it was often sweetened, cheaper than beer, and thus easily abused. Deeper down however, it still hearkens up a misty image of old farmers gathered in a cider shed around a barrel of scrumpy, an icon of rustic simplicity, the antithesis of industrialization.

This rural image, and the characters in it, are quickly slipping into a lost era, but that doesn’t mean that cider it going with it, or that an increasingly urban population has lost touch with its rural heritage. In fact, in the past 10 years, wassailing, a custom that had largely vanished, suddenly resurged.

Rooted in social and occupational customs of a more agricultural era, wassailing, which is reported by observers in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, involves a blessing of crops and animals on the twelfth night of Christmas, accompanied by visiting and sharing of food and drink. In the orchard regions particularly, the custom became associated with blessing the apple trees, singing to them, feeding them with cider and toast, and scaring away evil spirits to ensure a good harvest in the coming year. Usually there was a good deal of toasting, drinking, lighting of bonfires, and some pretty raucous behavior as well.

Wassailing today, as I have witnessed it, is often carried out almost entirely by people who have little or no connection to farming. But I think this is the most interesting part of this resurrected tradition. In a time when people have so little connection to the production of their food and drink, it is rather remarkable to see folks bundled up and tramping out to an orchard to sing to some trees and drink buckets of local cider. You could see it as an insubstantial appropriation of traditional culture that doesn’t really address the greater issues of agriculture and food production. And in some ways, this is true. But you can also see in it the great yearning for people to reconnect with their rural and agricultural heritage, to leave their modern warm, cozy lives for an evening and remember what it is like to be cold and excited by the flare of bonfires and the sharing of food, drink, company, and music.

While the upswing of cider as an industry in both the United States and the United Kingdom is trying to improve upon the scrumpy of old and introduce beautiful craft products to the large, discerning urban market, in the United Kingdom, cider also carries with it these cultural memories and rituals of a time before industrialism, a time when lives were ruled by seasonal labor and seasonal celebration and characterized by local distinctiveness and variety.

Those who are interested in finding interesting local ciders in the United States will likely find some available in regional markets such as the Northeast, the Northwest, and the Great Lakes. Personal favorites I have encountered in my travels in North America include:

- Sea Cider

- Left Field Cider from British Columbia

- Virtue Cider from Michigan

- Aaron Burr Cider from New York

- New Day Meadery from Indiana.

There are so many more to try, I can’t possibly name them all. Those interested should keep an eye on The United States of Cider or Cider Guide

for news on the cider scene. The serious maker with a business in mind might join the United States Association of Cider Makers.

For those interesting in reconstructing, resurrecting, or reinventing the tradition of Wassail, you might be interested in a recipe to fill communal wassail bowl itself. The following passage from historian Roger French’s book The History and Virtues of Cyder, resurrects a forgotten class of drinks called posset, syllabub, or wassail, which combine alcohol (cider, beer, or wine, as the case may be) with spices, cream, eggs, and sometimes oatmeal or grain. French borrows a recipe for posset from earlier seventeenth writer Sir Kenelm Digby and suggests substituting cyder for wine:

Boil a pint of cream with a little cinnamon and mace. Beat well two whole eggs and the yolks of two more and stir into a quarter pint of sack [cyder] and then add three ounces of sugar with a little grated nutmeg; bring almost to the boil. Pour on the hot cream from some height, but do not stir. Cover with a dish, and when settled sprinkle with a little [caster] sugar with a touch of some ambergris and musk on top.

For more on cider and wassail:

Brown, Pete, and Bill Bradshaw. 2013. World’s Best Ciders. Aurum Press, Limited.

Common Ground (Organization). 2000. The Common Ground Book of Orchards : Conservation, Culture and Community. London: Common Ground.

Crowden, James. 1999. Cider – the Forgotten Miracle. Somerton: Cyder Press 2.

Di Palma, Vittoria. 2004. “Drinking Cider in Paradise: Science, Improvement, and the Politics of Fruit Trees.” In A Pleasing Sinne: Drink and Conviviality in Seventeenth-Century England, edited by Adam Smyth. DS Brewer.

Freeman, Eric. “My Country Life: The Wassailer | Countryfile.com.” 2012.

French, R.K. 2010. The History and Virtues of Cyder. Robert Hale Ltd.

Morgan, Joan. 2013. The New Book of Apples. Random House.

Palmer, K., and R. W. Patten. 1971. “Some Notes on Wassailing and Ashen Faggots in South and West Somerset.” Folklore 82 (4) (December 1): 281–291.