Hana began foraging as a child during family camping trips. She started with lemonade berries and has branched out over the years to mushrooms in the Rockies, juniper berries in New Mexico, cattails in the Berkshires and anything she can find in New York. She works fulltime as a financial journalist and part time as a birth doula.

The urge to collect attractive natural things has always been part of my psyche. Pine cones, interesting seeds and leaves, and unusual rocks often make their way into my pockets. Even though I live in Manhattan, I am constantly finding things to collect — especially edible things.

I have had great luck in the city with mushrooms and berries. Greens (mustard, mint, herbs, etc.) tend to grow in places where dogs pee, and there is always a question of what pesticides may have been sprayed. Roots (burdock, carrot) are often not large enough to be worth digging and can be contaminated with pesticides or other soil pollution, too. Digging also can draw attention to an activity that is technically illegal in New York City.

Central Park Mushrooms

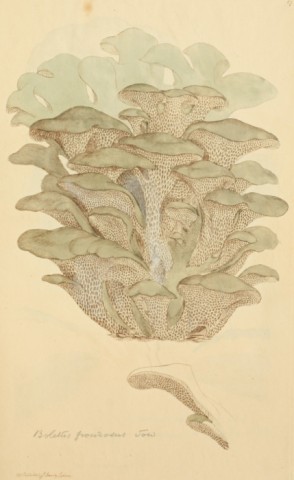

Mushrooms, whether urban or forest, give me so much pleasure to find and identify that I enjoy finding them even when they prove inedible. Beautiful organisms, they occupy a space between growth and decay as they work to transform dead plant matter into nutrients for the next generation, and lend help to trees in extracting minerals from the soil. They are unpredictable but when they do show up it is often in droves.

One of my most memorable catches, a heavy haul of hen-of-the-woods mushrooms, a gray-brown polypore that grows with oaks in the fall, took me and my husband by surprise. We were walking through Central Park to visit a friend when we found them. First through the North Woods, then out to West Side Drive and south to the pinetum near the 85th Street exit.

After so many years of collecting, my eyes are exquisitely attuned to anything unusual, so I immediately noticed the brownish fronds decorating the base of a big old oak. The oak was behind a chicken wire fence, a fabulous sign as far as urban foraging goes: even dogs off their leashes don’t jump fences.

It seemed magical, the way they appeared under large oaks where there had previously been only flat earth. By the time we reached our destination we had spotted more than we could carry and made off with the best fifteen pounds we found, carrying them in scrounged plastic bags.

Tree Fruit on the Bike Path

As for fruit, I have become familiar with six prolific juneberry trees (a member of the rose family) on the West Side Bike Path, and two extremely prolific cornelian cherry trees (a species of dogwood) next to them. Juneberries are good on their own, though they are a little mealy and not as sweet as the blueberries they closely resemble. Cornelian cherries are pungently sour and difficult to eat plain, but wonderful in pies, jams, and chutneys. Supposedly they can be pickled. These two types of tree pop up all over the city — for example, in the plaza at the 72nd Street 1, 2, 3 subway stop.

And then there are apples (also a rose relative). New York is chock full of apple trees bearing fruit of varying size, color and edibility. Many of them are the size of peas or small grapes with an astringent taste that makes your mouth feel squeaky and turpentinish. None are as large and sweet as supermarket apples but every once in a while you find a tree bearing fruit the size of cherries, perfect little pink and green apples with a unique sweet tartness.

I have found a few of these. One fall I hauled away around twenty-five pounds of these beauties, in multiple trips, from a single tree on the Upper West Side. Those, in addition to being eaten ravenously by themselves, became apple pie, hard cider and apple butter.

Other edible delights that show up everywhere include mulberries, blackberries and cloudberries, plantains, chives and herbs, inky caps, fairy ring mushrooms, chicken of the woods, day lilies, violets, milkweed, and bluebells.

A Note on Identification

To forage safely, you must view identification as a puzzle. If you have solved the puzzle perfectly, you can eat the plant or mushroom in question. If you are pretty sure you have solved it, you cannot eat it.

It’s best to use multiple field guides. You need to have a detailed written description, a good photo and a faithful artist’s rendering; few if any guides have all three. It is also good to have a sense for the larger region as well as varieties specific to your locale, and solid edibility information. Some field guides, most notably those dealing with mushrooms, do not have reliable indications of whether something is edible or not.

For mushrooms, I have used a combination of the Peterson Field Guide, which has good drawings and descriptions, and David Arora’s Mushrooms Demystified

which has photos, descriptions of look-alikes and trustworthy edibility information. I also quite like the Audubon Society Mushroom Guide

in place of the Peterson. Experiment with combinations of field guides to see what works for you.

You will get the most out of foraging when your pleasure in discovering and identifying matches your pleasure in eating, and when you realize that edibles grow everywhere.