I have not written here about the Occupy movement, or about very much else to do with politics either, in part because I had conceived of this space pretty narrowly. And though the masthead reads Cooking, Eating, Politics, just cooking and eating seemed like more than enough to deal with.

But given recent events in Philadelphia, I have largely changed my mind. Last night, a couple of hours past midnight, the police finally moved in to evict Occupiers outside of City Hall. I say finally, because Mayor Michael Nutter originally told them that they had to be out on November 14th. And then he told them, for certain, that they were to be evicted at 5:00pm on November 27th. Neither eviction happened, the latter, in no small part, because more than one thousand people gathered to stand with the Occupiers against the city.

And so this time, the eviction wasn’t announced. Police moved forward in riot gear and on horseback, at first pushing protesters back, out of Dilworth Plaza, and then charging into the crowds. As the Occupiers organized to leave — as they started marching out of the plaza toward Rittenhouse Square, where they planned to regroup — police on bicycles chased them, blocking intersections and making it difficult for them to move. By one estimate, more than two dozen Occupiers were arrested. One was trampled by a horse, her foot broken. While others were run down by bicycles, or had bicycles thrown at them, as they tried to march away.

This violence against Occupiers is not unique. And frankly, to the credit of the city, Occupy Philly has been less marred by deliberate and casual brutality than has Oakland or Seattle, U.C. Berkeley or Davis, or even than New York. Those places, I’m sure that I need not remind you, have seen violence of a sort that is difficult to fathom, at least by me: dozens injured in Oakland, including one Iraq War veteran who had his skull fractured by a tear-gas canister fired at close range by police; a pregnant nineteen-year-old kicked in the belly, and an eighty-four-year-old woman pepper-sprayed by police in Seattle; students and faculty, including former Poet Laureate of the United States Robert Hass, beaten with batons in Berkeley; tents cut up with knives, and thousands of books carted away, by the Department of Sanitation in New York.

All things considered, Philadelphia has been spared. But still, violence is violence, especially against people who pose no imminent threat to public safety, who are themselves philosophically against violence, who are mostly unarmed, and who have said repeatedly, and to the Philly P.D., that they are willing to let the eviction proceed. They are just unwilling to do anything to aid in its implementation.

The Mayor, in a press conference early this morning, said that Occupy Philly has changed — that the movement has chosen not to work with the city, that they are in violation of their permit and of city health and safety codes, and that they are standing in the way of a thousand new jobs, in the form of a renovation project on City Hall.

But none of these reasons are very convincing, especially considering the ugly light this shines on a city already blackened by a history of police violence; especially considering the Mayor’s previous and continued insistence that he believes in the goals of the Occupy movement, and that he stands, in his words, with the ninety-nine percent; and especially considering, as we learned the other week, that mayors across the nation have coordinated with each other, and perhaps with the Department of Homeland Security, to shut Occupy sites down.

Why, then, the resistance? Why are folks in authority are so frightened of a horde of non-violent (if slightly ripe) protesters that they act against all good judgment — against sensible PR and against fidelity to the documents they have sworn to uphold — just to make them go away? And why do they do this even as they stare baffled at the television cameras and proclaim to viewers at home that these people don’t even have an agenda — that beyond vagaries and unrealistic manifestos, they have nothing coherent to say?

The issue, I think, is that Occupiers do in fact have something to say. They are saying it pretty clearly. And even if individuals on the ground cannot articulate the message, their presence — the fact that Occupiers are being seen, and the fact that they are committed enough to have spent two months doing this at their own peril — speaks volumes.

My thinking on this is influenced a great deal by a series of lectures that Judith Butler gave at Bryn Mawr college over the past month. In them, she made the argument that a call for justice — the fight against the notion that individuals or whole populations are disposable — exceeds any specific demand. She argued that presence, public assembly, constitutes a demand in and of itself: a demand to be seen, an assertion that we are here and we must be accounted to, an assertion of the right to be (and to be represented), just the same as groups who do not face conditions of precariousness.

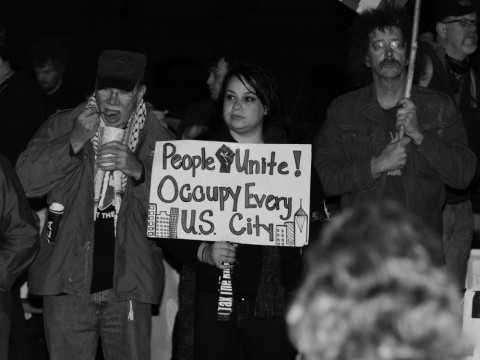

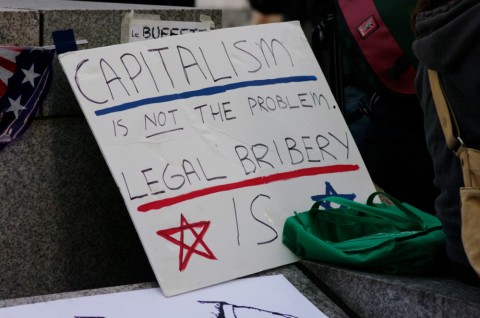

She, of course, was more eloquent than I am. But her point was that the specifics of what is on Occupiers’ signs is less immediately relevant to their message than their persistent presence. It is less relevant than the fact that this group of people — a coalition that crosses traditional political boundaries and that crosses specific interest in specific issues (feminism, workers’ rights, LGBT, etc.) — all agree that something has gone terribly wrong, that it is to do with collusion between the banks and government, and that the situation is so intolerable (and we are so little represented as a result) that change on a large scale needs to happen now.

Are there weaknesses in the Occupy movement? Sure. And the specifics of what is on their signs is one of them. So is the fact that they have been unable to choose spokespeople who can articulately represent the movement to the media. So is the fact that they have allowed the media to continually misrepresent their internal democratic process. So is the fact that they have, at least sometimes and in some respects, courted conflict with the police as a way of gaining attention.

But none of these things detract from the message of the movement. And none of these things suggest that their message is not sophisticated. Paul Krugman, who I otherwise admire a great deal, is wrong on this point. The idea is not to point out the broken-ness of the system, and then force policy experts to make the right kind of changes. The idea is that the Occupiers are out there being the kind of change that they want to see. They are helping and supporting one another where they live; they are working to aid the homeless and the mentally ill; in many places, they are going out into the community to stop banks from foreclosing on houses. There is also crime, and cruelty, and certainly poor sanitation going on in the encampments. But to my mind, that is no less a part of the message: what Occupy is about isn’t utopian or pie-in-the-sky. It is about a return to empathy, a return to an ethic of care, a return to the notion that there is such a thing as public good, and that it should not be co-opted for the benefit of a select few, at the cost of the many.

How could any of this be implemented on the Federal, or state, or municipal levels? Watch me shrug. I have some pretty strong convictions about the matter. But they are mine, not the movement’s. And maybe this is where Paul Krugman has a point.

Nonetheless, this notion of presence is what makes the Occupiers so dangerous to folks in charge. I call them protesters, but they aren’t protesting so much as modeling, on the streets, a different kind of relationship between individuals, business, and government. And it is a model that doesn’t include people like Michael Bloomberg, or political machines like the Philadelphia Democrats, or certainly the Department of Homeland Security. Theirs is a model that would offer preference to individuals, not corporations, that would limit the flow of money from corporations into politics, and the flow of talent from politics into corporations. And theirs is a model that would replace politicians who do not represent their constituents.

And above all, I hear the politicians all shout at once — above all, we cannot have that.